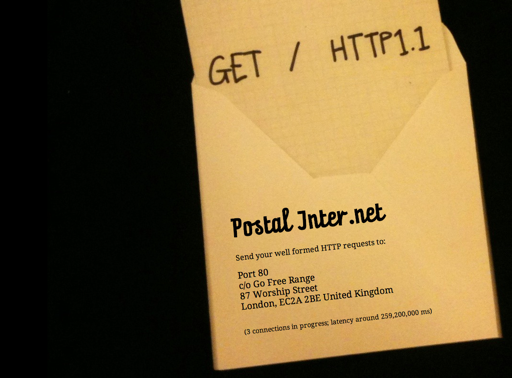

Postal Inter.net

We at Free Range have decided that, now we’ve settled into a reasonable groove, 2011 is going to be the Year Of Shipping Ideas. Instead of just musing about fun things and then letting them fester on untouched mental todo lists, lets just get stuff built and move on to new things. Leila Johnston says it pretty well.

With that in mind, I had a whimsical idea the other day, but rather than just feel privately smug for a few minutes (like I normally do), I knocked it up and threw the mewling infant out into the world to fend for itself.

It’s called postal inter.net. I don’t want to say much more about it, since part of it’s charm is for you folk to explore what it is. All you need to join in is some paper, envelopes, and a few stamps.

We’ve already got one established connection in progress, but it would be great to have more. I know it takes an extra bit of effort to do things in the “real world”, than just clicking a link, but hopefully a few of you will join in our little jape.